When I was a child, I was taught in church that the words Christian and Nazarene were synonyms, and that they referred to the same group of people. Years later, I realized that this was not correct. One of the Catholic Church founders, Epiphanius of Salamis, wrote a book in the early fourth century called Panarion (Against Heresies), in which he condemned a group called the Nazarenes for practicing Jewish Christianity. That is, the Nazarenes believed on the Messiah, yet they still kept the original Jewish rites of circumcision, the Sabbath, and the laws of Moshe (Moses).

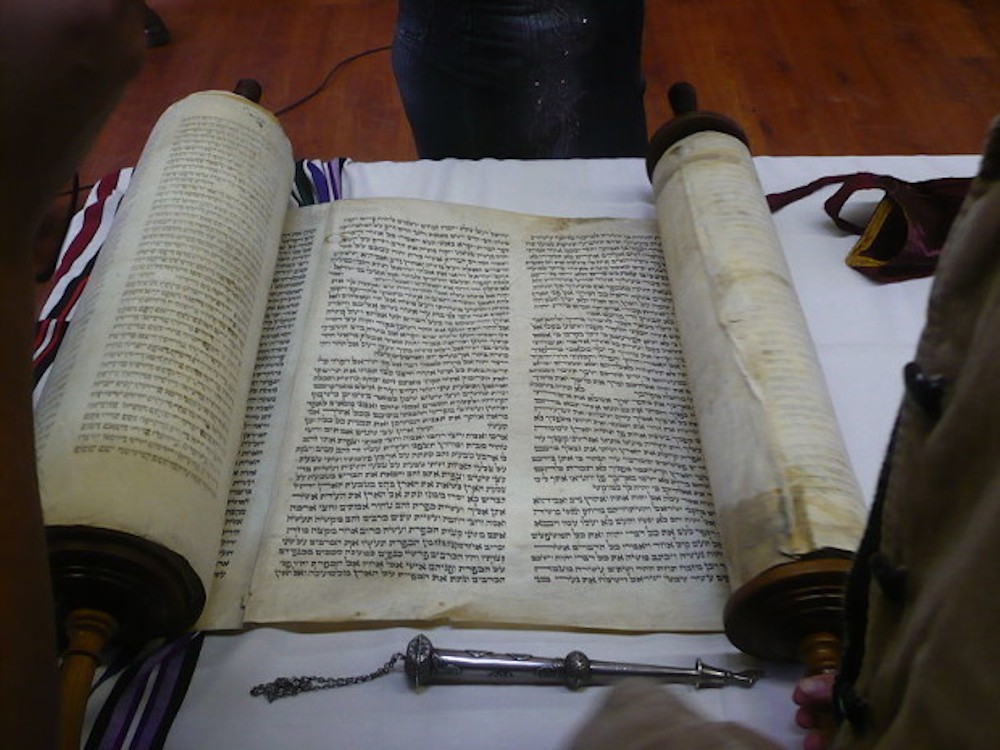

The Nazarenes do not differ in any essential thing from them [the Orthodox Jews], since they practice the customs and doctrines prescribed by Jewish Law; except that they believe in Christ. They believe in the resurrection of the dead, and that the universe was created by God. They preach that God is One, and that Jesus Christ is His Son. They are very learned in the Hebrew language. They read the Law [the Law of Moshe]…. Therefore, they differ…from the true Christians because they fulfill until now [such] Jewish rites as the circumcision, Sabbath and others.

[Epiphanius of Salamis, “Against Heresies,” Panarion 29, 7, pp. 41, 402]

Since Epiphanius was Catholic, his condemnation of the Nazarenes meant that the Catholic Christians and the Nazarenes could not possibly have been the same group of people—but they were two separate groups.

Yet if the Messiah and His apostles were Jewish, why did Epiphanius condemn the Nazarenes for practicing Jewish Christianity? To answer that question, let us look at the works of Marcel Simon, a late Catholic expert on the first century. Even though Marcel Simon was a devout Catholic, he disagreed with Epiphanius, saying that Epiphanius knew that the Catholic Church did not descend from the apostles.

“They [Nazarenes] are characterized essentially by their tenacious attachment to Jewish observances. If they became heretics in the eyes of the Mother Church, it is simply because they remained fixed on outmoded positions. They well represent, [even] though Epiphanius is energetically refusing to admit it, the very direct descendants of that primitive community, of which our author [Epiphanius] knows that it was designated by the Jews, by the same name, of ‘Nazarenes’.”

[First Century expert Marcel Simon, Judéo-christianisme, pp. 47-48.]

Marcel Simon tells us Epiphanius knew it was the Nazarenes who descended from James, John, Peter, Paul, Andrew, and the rest; yet both Epiphanius and Marcel Simon called the Nazarenes “heretics” because they continued to keep the same faith the Messiah had taught them. But isn’t that what Scripture says to do?

Yehudah (Jude) 3

3 Beloved, while I was very diligent to write to you concerning our common salvation, I found it necessary to write to you, exhorting you to contend earnestly for the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints.

If Jude tells us to “contend earnestly” for the faith which was “once for all” delivered to the saints, then isn’t that the faith we should keep?

As I began reading more about the Catholic Church, I began to see that there were many in the Catholic Church who felt that somehow they had the authority to change what the Scriptures taught.

“Some theologians have held that God likewise directly determined the Sunday as the day of worship in the New Law, [and] that He Himself has explicitly substituted the Sunday for the Sabbath. But this theory is now entirely abandoned. It is now commonly held that God simply gave His Church the power to set aside whatever day or days she would deem suitable as Holy Days. The Church chose Sunday, the first day of the week, and in the course of time added other days as holy days.“

[John Laux, A Course in Religion for Catholic High Schools and Academies (1936), vol. 1, P. 51.]

Was John Laux saying that the Church had the authority to change the Father’s word? What sense did that make? It didn’t make any sense, but other Catholics asserted the same thing.

“But you may read the Bible from Genesis to Revelation, and you will not find a single line authorizing the sanctification of Sunday. The Scriptures enforce the religious observance of Saturday, a day which we [the Church] never sanctify.”

[James Cardinal Gibbons, The Faith of our Fathers, 88th ed., pp. 89.]

Many high-ranking Catholic Church authorities admit that the Catholic Church had changed the days of worship on her own.

“Question: Have you any other way of proving that the Church has power to institute festivals of precept?

“Answer: Had she not such power, she could not have done that in which all modern religionists agree with her-she could not have substituted the observance of Sunday, the first day of the week, for the observance of Saturday, the seventh day, a change for which there is no Scriptural authority.”

[Stephen Keenan, A Doctrinal Catechism 3rd ed., p. 174.]

Thus, the Catholic Church claims it had the power to change the days of worship simply because they did it (and got away with it.) That doesn’t match up with Scripture at all! Instead, we are told not to add or take away from His word.

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 12:32

32 “Whatever I command you, be careful to observe it; you shall not add to it nor take away from it.”

The Creator had told Israel to keep the seventh-day Sabbath (Saturday) as His official day of rest, and it was never prophesied that it would change.

Shemote (Exodus) 20:8

8 “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it set apart (holy).”

What happened? Had the Catholics suppressed the original Nazarene Israelite faith? And if so, then how can we rebuild the original faith for those who want to practice it?

And can we verify all of this from Scripture? Do the Scriptures tell us there were two separate groups of people in the first century, the Christians and the Nazarenes? And if so, then to which group do the Scriptures say the apostles belonged?